Climate Justice

This year the floods in Pakistan have returned displacing 5 million and killing hundreds. Last year's floods were the worst in living memory with 20 million affected and 2,000 killed. Last year also saw record breaking temperatures in Russia with wildfires and crop failures while this year we have seen the latest in a series of exceptional droughts in East Africa causing famine in Somalia.

The frequency and severity of weather related disasters is on the increase and scientists tell us this is due to human-induced climate change caused overwhelmingly by the high emissions and high consuming lifestyles of richer countries like our own.

International climate negotiations have been foundering. In Copenhagen and Cancun, richer countries have shifted the direction away from legally binding targets and towards voluntary pledges that, even if implemented, would see a shocking 4C average rise in global temperatures by the end of the century.

As rich countries procrastinate, the poor of the world are already suffering the impacts of climate change: in other words, the people who have done least to cause the climate crisis. Poor people tend to live in the most vulnerable locations and lack resources to adapt. A two degree average rise in global temperature has been adopted as a 'safe limit', however this would mean much greater rises in some parts of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa. Agricultural systems in the drier regions of Africa are already on the limit of tolerable conditions.

What does Climate Justice mean?

Reducing the risk of climate destabilisation by cutting global carbon emissions fast

As emissions cuts are delayed, more CO2 builds up in the atmosphere, accelerating the rate of warming and increasing the risk of triggering positive feedback mechanisms (see more information about the Climate Emergency). Those who will bear the consequences are not decision-makers in rich countries, but poorer countries first, then future generations.

Rich countries make much greater emissions cuts than poorer ones

This is the only justifiable approach. First, per capita emissions are so much higher in rich countries. For example, an average US citizen emits around 18 tonnes CO2 a year, an average UK citizen around 8.5 tonnes, a Chinese person around 5.8 tonnes and an average Indian around 1.4 tonnes. Across the whole of Africa the average is just 1.1 tonnes. (Crucially, if you count emissions by the country where goods are consumed, UK totals would rise by around 50% and China's would be halved). Clearly there is a lot more scope for rich countries to cut emissions without affecting the wellbeing significantly. In contrast, the poorest countries should be allowed to increase their emissions to allow for basic development needs.

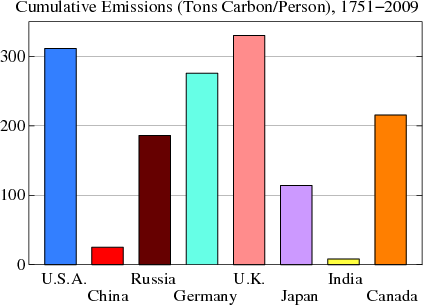

Second, the excess CO2 now in the atmosphere has built up over a long period of industrial development in richer countries. This industrialisation has enabled countries like the UK to build up wealth, infrastructure and political power - but the waste products are pushing the planet to the brink of catastrophe. These countries therefore bear an even greater moral responsibility for climate change.

Second, the excess CO2 now in the atmosphere has built up over a long period of industrial development in richer countries. This industrialisation has enabled countries like the UK to build up wealth, infrastructure and political power - but the waste products are pushing the planet to the brink of catastrophe. These countries therefore bear an even greater moral responsibility for climate change.

See graph (right) from James Hansen's book 'Storms of my Grandchildren'

Rich countries provide adequate funding for adaptation and low-carbon development to poorer ones

Poorer countries should not be expected to bear all the costs either of adapting to climate change or of implementing low-carbon technology. This funding has been promised as a key part of international climate negotations, but there are major question marks over how the funds will be raised, the involvement of the World Bank and the provision of money as loans rather than grants: 86 per cent of the UK’s finance for adaptation will be given as loans, increasing the debt burden of world’s poorest countries.

Resources

- Oneworld.net briefing on climate change and poverty

- WDM's guide to climate justice issues at COP17 in Durban

- Data on countries' emissions from the Guardian

- Find out more about the science of climate change and what we need to do - download the Climate Emergency pamphlet

Last updated Dec 2011